Where the fish go crazy (4)

'Water has no DNA, but could it have memory?'

2026

Floor

DATE

Aug 14, 2024

WRITTEN BY

Valerie van Leersum

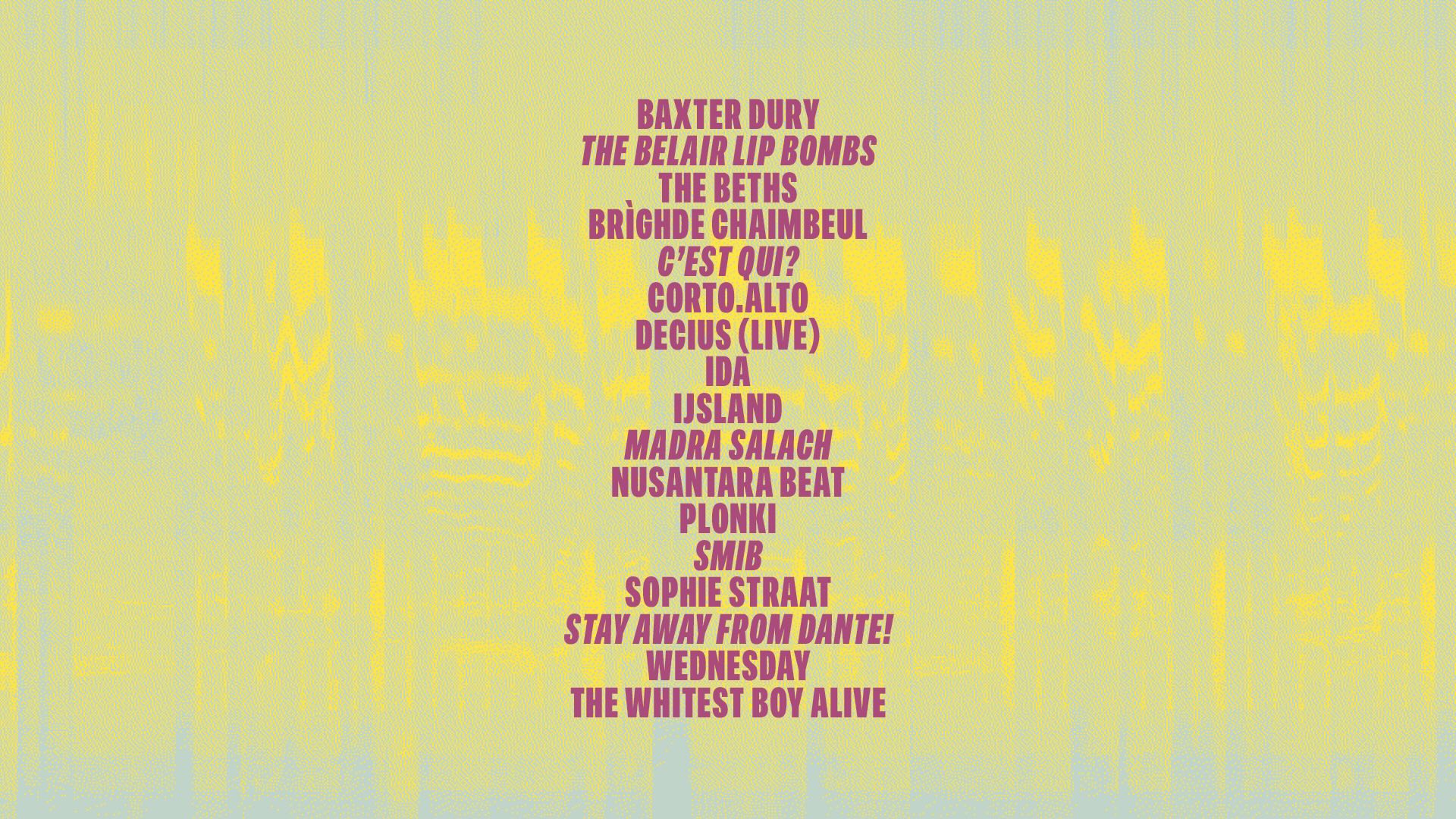

Mister Motley and Into The Great Wide Open join forces to unlock the research of artists for a broader audience, such as that of Valerie van Leersum, who will present a work that is part of the art route from Into The Great Wide Open this summer on Vlieland.

A island is defined by the dictionary as 'land that is surrounded by water on all sides and does not form a continent.' In the case of Vlieland, that water consists of two seas: the North Sea and the Wadden Sea. Unique places, each with a completely distinct identity. But where do these two seas meet? Is there a border? How do they relate to each other, and what does that connection look like?

In the coming time, artist Valerie van Leersum will be dealing with these questions: a research project that will culminate in a (visual) work that will be shared with the public during Into the Great Wide Open 2024. Around the yearly theme Shifting Perspectives, about ten artists will present their work both during the day and in the evening in the overwhelming nature. In the lead-up to the festival, Van Leersum will stay on the island several times as an artist in residence and will investigate both the color of the North Sea and the Wadden Sea, and engage in conversations with various island residents about their knowledge and vision concerning the place where these seas merge. Mister Motley and Into The Great Wide Open join forces to unlock the research of artists for a broader audience. Through our respective channels, we will share Valerie's quest for the alleged border that lies in the water and what it can teach us. During my stay on the island, I will read the dissertation written by Marcel Robert Wernand on the Forel-Ule scale: Poseidon’s Kleurdoos. The Forel-Ule scale is a method to determine the color of water bodies, approximately.

For this determination, a measuring instrument consisting of 21 transparent glass tubes, each filled with a chemically mixed liquid in a color gradient from dark blue to deep brown, is used. The method is used in combination with the Secchi disk, which determines the transparency of the water. Together, they are among the oldest oceanographic parameters; they date back to 1890. Marcel's dissertation discusses many facets, findings, and theories related to observations and analyses of the color of the sea. For instance, it looks at the color of our water in relation to climate change and links old methods of measuring color to contemporary measurements from satellites.

I find it very exciting to read about the many ways that have been tried over the years to determine the color of water and the statements of people who have attempted to articulate these findings earlier. Such as: 'Everything related to the color of water is exceptionally problematic.' Written by Von Humboldt in 1815.

The color of water has intrigued us for a long time, and we have long suspected that it tells us something. But what exactly do the 21 colors of the Forel-Ule scale represent? A question for which I find no answer while reading the thesis. I decide to use my self-imposed scarce ChatGPT ration on this question. 'Do you know what the 21 colors of the Forel-Ule scale stand for?’ I ask her. 'Sure. Although the exact conditions can vary somewhat depending on interpretation and environmental factors, the general characteristics of each color are as follows.’ And then, one by one, the color numbers and their conditions appear on my screen. No. 3: Greenish white (Vert-Blanc): Milky or cloudy water with poor transparency and a greenish tint, indicating high turbidity and suspended particles. No. 12: Dirty yellow (Jaune-Sale): Yellowish water with poor transparency and high turbidity, likely containing suspended sediments or pollutants.

A bit disappointed, I look at the answers to my question. I do not know what I had expected, but apparently hoped for something different than this rather logical outcome. The solidity of the framework seems so far removed from the elusive nature that I and presumably other seekers of the color of water are seized by. The movement of color, in time and place. And that is exactly what I want to incorporate into my work for the festival. The border, the color, the movement, the elusive.

Color tests in the studio. Photo: Valerie van Leersum. As agreed, Folkert and I meet at the café ’t Praethuys where we continue our conversation about the sea, its color, and boundaries that we had during our earlier meeting in the Vliehors Expres. I ask Folkert about the difference between the two waters. 'The composition of water in the North Sea is different from that in the Wadden Sea, but it’s always H2O,' he says. ‘Recently I read a piece about epigenetics,’ I tell him. 'It explores whether information that is not found in the DNA can still be passed from one generation to the next. Water is a molecule, not an organism, therefore it has no DNA, but could it possibly have memory, I wonder? Are its traumas stored, its wisdom and adventures passed down?' 'Ha! now our conversation is turning into philosophical physics. That’s not really my field, but let’s give it a try. Everything has a vibration. This can be influenced by the conditions in which it occurs. But I wonder to what extent that vibration can be remembered or passed on. I cannot imagine what utility and effects that could have in nature. And without utility, something in nature has no right to exist. Nothing is accidental.'

Continuing our conversation, Folkert and I reach the melting ice caps, the mixing of salt and fresh water and the major ocean currents. I show Folkert the cards with the colors of the sea. 'That will be interesting,' he says, 'because I am colorblind. But I can certainly indicate what I perceive.' He chooses a color: 'this is behind the Vliehors on the side of the Wadden Sea, it’s a bit grayish blue.' I also see a hint of purple in the color, but pastel colors are hard for Folkert to perceive. He resolutely flips through the colors and knows precisely what he is looking for. To my surprise, he says, 'I miss brown-blue.' Brown-blue is a color I can’t see immediately, and that doesn’t happen often. 'There’s a hint of yellow in it,' he explains. That is the color of the mudflat.

‘The next time you are on the island, I’ll take you on a mudflat excursion; then you’ll encounter a completely different perspective on color.’ With this promise, we each go our separate ways. Before cycling away, I receive a final piece of advice from Folkert with a smile: 'Don’t forget: take the time and space to be adventurous, then unexpected things can happen.'

Color tests on Vlieland and in the studio. Photo: Valerie van Leersum.

The Line

On the last day, I decide to pull two enormous wooden disks onto the beach. I brought them to play with. I want to let the circles, as a symbol of everything that is connected, move in the place where two seas possibly meet. The circles, 120 cm in diameter, have a small slot and interlock. The ratio is critical, but when it’s correct, they move beautifully together in the wind.

Pulling on the two large shapes, I feel like a little crab on an immense beach, searching for the movement of wind and water. When these two elements take over from me and I let go of control, it’s just as thrilling as it is fantastic. The disks roll around each other. Sometimes they stand still for a moment, searching for the wind, only to then take off with an increasingly faster rotation. At times the force of it takes my breath away, other times I run after them squealing like a child. To my surprise, I discover they leave a beautiful trail in the sand.

I will carry on with this. It is exciting and unpredictable, but perhaps that’s exactly what makes it so fitting for the place and the stories I have heard about it.

Soon in the studio, I will paint the disks in the colors of the Forel-Ule scale. One disk in the color of the North Sea, the other in the color of the Wadden Sea. Together, the colors alternate.

Ungraspable as a boundary in the water. An invitation to reflect on the beautiful complexity of the world around us and our place within it. Playful, collaborative, letting go, and embracing.